Introduction

It

has been both euphemistically and derisively called an “attack in another

direction” and the “Big Bug-Out,” and candidly described as a

“miracle,” as “an exercise in improvisation,” and as “the first and only

amphibious operation in reverse” in U.S. military history; but the

unarguable truth is that the Hŭngnam evacuation stands alone as one of the

greatest epic campaigns of the Korean War. Over the course of two weeks,

the legendary and controversial X Corps would fight its way to the sea along

a harrowing route through the mountains of eastern North Korea, destroying

two Chinese armies along the way, before reaching the sanctuary of the

Hŭngnam beachhead, where it would integrate the 105,000 U.S., U.N. and

ROK military personnel, which,

along with 17,500 vehicles, 350,000 tons of cargo, and 91,000 refugees, were

to be evacuated in the largest sealift since World War II.

The time-honored maxim of the “first one in, last one out”

has never been so aptly embodied as it was by one small outfit of the 3rd

Division. The division’s vanguard regiment in Korea, it would also be the

corps’ rearguard during the corps’ evacuation. It went by the soubriquet

“The Borinqueneers.”

The

“Home-by-Christmas” Campaign

Failure

after failure had been the order of the day for the North Korean People’s

Army (NKPA) following the X

Corps’ successful landing at Inch’ŏn in September. Douglas MacArthur’s

United Nations Command (UNC) had

put the smashed remnants of the NKPA

in a rout north; had captured the North Korean capital of P’yŏngyang by

mid-October; and had been in hot pursuit of the communists ever since.

During the Wake Island meeting with President Truman, the general had

assured his commander in chief that the possibility of Chinese intervention

in Korea would be minimal. The Chinese commies would not attack; the allies

had won the war. The President could send a division to Europe from Korea

as early as January 1951.

The

“imminent” success, reasonably, inspired the Supreme Commander Allied Powers

(SCAP) and Commander in Chief,

United Nations Command (CINCUNC)

to utter the outrageous promise to have “the boys back home by Christmas.”

Per

MacArthur’s instructions, Lt. Gen. Walton H. “Johnnie” Walker, commanding

general of the Eighth U.S. Army, Korea (EUSAK),

and Maj. Gen. Edward M. “Ned” Almond, commanding general of the X Corps,

rushed their respective “armies” in a northward race to the Yalu River.

Whether they were to cross the river and carry the war into Manchuria

remained to be said. Neither man foresaw – perhaps both men rather chose to

overlook – the possibility that differences between the two forces, both

geographical and personally speaking, could seriously cripple their

collective effectiveness. Firstly, since its arrival in Korea, X Corps had

been operating as an independent army rather than assuming its subordinate

status to EUSAK.

Secondly, the commanders’ dislike for one another exacerbated this awkward

arrangement.

Parting from the premise that the communists were defeated and the boys

would be home by Christmas, the armies continued their advances in a total

of four parallel but dispersed columns, leaving the meridian part of Korea

open to … anything.

The

race to the Yalu came to an abrupt halt on the night of November 25, when

200,000 Chinese Communist Forces (CCF)

troops attacked the

EUSAK

lines.

Enter

the Dragon: Douglas MacArthur Pays Dearly

Rumors of an increasing Chinese intervention in the war had

spread like wild fire all over Korea – its flames lapping at the steps of

MacArthur’s General Headquarters in Tokyo, and its smoke starting to collect

in Truman’s office in Washington, D.C. MacArthur decided to hush the

rumors, preferring to save face and live up to his assertion at Wake

Island. Should it hit the fan, it had been his own G-2 who first

dismissed the possibility of Chinese intervention.

Having landed in North Korea at the end of October, the 7th

“Bayonet” Division’s 17th Infantry Regiment became the first unit

of X Corps to reach the Yalu unopposed.

South of the 17th, sister regimental combat team (RCT)

32nd had set up a forward command post east of the enormous

Changjin (Chosin) Reservoir. A stone throw south of the 32nd,

the 1st Marine Division sat astride the artificial reservoir

while headquartered at Hagaru-ri. The 31st RCT and the Republic

of Korea Army (ROKA) I Corps stretched in an arc anchoring the northeastern

part of the peninsula.

During a hasty visit to the 32nd RCT the day after the CCF attack

on EUSAK,

Ned Almond accepted the rumors, yet emphasizing that there were not two

divisions in the whole of North Korea. The Chinese they had been talking

about were

“nothing more than

some remnants of Chinese divisions fleeing north.” His X Corps was still

attacking and was going all the way to the Yalu. He further spurred his

commanders to continue and not to “let a bunch of Chinese laundrymen stop

you.”

The

plan had been that once North Korea had been cleaned up, the

ROKA would take over and the UNC would pull out of Korea. His

“incomprehensible” strategy now had X Corps fragmented across a huge front.

West

of the unguarded EUSAK–X Corps boundary, Johnnie Walker was unable to repel

the CCF onslaught. One dumbfounded Douglas MacArthur could only watch as

Walker’s decimated troops pulled a “180” back to the 38th

Parallel. East of the boundary, rumors became reality overnight: There

were not two Chinese divisions in North Korea, as Almond had said.

There were two armies!

Before long, on MacArthur’s orders, Almond was to instruct the 7th

Division forces on the Yalu to fall back on Hamhŭng, an industrial city

northwest of Wŏnsan, where the general had established his Corps

Headquarters. Once there, the rearguard division troops were to protect the

corps’ northern and northeastern flank, establishing a strong position 20

miles north of Hamhŭng, to block roads leading south out of the area to be

vacated. At the same time, the ROKA I Corps was to protect the right flank

and secure the east coast road as the forces completed their movements

south.

The Tip

of the Spear

The

65th Infantry Regiment had joined the war as a last-minute

addition to the 3rd “Rock of the Marne” Division before departing

Puerto Rico in August.

The division’s only regiment in Korea, it had been indiscriminately and

temporarily attached to the 2nd and 25th

U.S. divisions during EUSAK’s

IX Corps pocket-clearing operations along the Naktong Bulge for the latter

part of September and most of October. The glory it had been denied for

missing out on the Inch’ŏn landing came calling when the shorthanded X Corps

called for additional support in the invasion of North Korea.

Never had the 65th Borinqueneers imagined that

their disembarking on the beaches of Wŏnsan in the first week of November,

hard on the heels of the 1st Marine Division, would mark the

beginning of a new kind of war with a new “enemy”: the controversial Ned

Almond. Not only would they undeservedly win the prejudice and

discrimination of their new corps commander, but would be at his mercy as

well. No sooner had the regiment’s advance party landed than Almond

fragmented it, putting it under the operational control of X Corps without

notifying the regimental commander. By rushing Lt. Col. Herman W. Dammer’s

2nd Battalion (2/65) into the mountains of nearby Yŏnghŭng,

piecemeal and lacking adequate ammunition to repel the suspected enemy force

hiding there, Almond virtually delivered the outfit to the enemy on a silver

platter. An opportune spotter plane would save the day by alerting the

allies to the Borinqueneers’ presence and by arranging an airdrop that

permitted the Puerto Ricans to repel the enemy and return to Wŏnsan.

Col.

William W. “Bill” Harris, commander of the 65th Infantry Regiment.

Near

Wŏnsan, November 1950 (National Archives)

When

the rest of the regiment landed at Wŏnsan, Almond immediately scattered it

all over the place: one part to “palace-guard” his headquarters, another to

bodyguard the 1st Marine Division elements there, and the other

to prepare for a westward venture aimed to contact and assist the decimated

EUSAK in Tŏkch’ŏn, near the

infamous boundary. To Col. William W. Harris, commander of the 65th,

the words of his 1930 West Point classmate and crony Aubrey Smith a few

nights earlier (“I wouldn’t go where you are being sent unless the corps

commander gave me … at least four infantry divisions.”) cast an ominous

shadow in his near future. The corps commander would indeed have to

reinforce Bill Harris’ outfit with a corps-sized force. The 3rd

Division, about to complete its training in Japan, would not arrive until

mid-November. (The need of reinforcements in Korea deemed necessary the

inclusion of the 3rd Division.)

The Tale

of Two Task Forces

From

the moment the rest of Maj. Gen. Robert H. “Shorty” Soule’s 3rd

Division arrived in North Korea, it would go on to block the road coming

east from Sach’ang-ni, and to protect the Wŏnsan–Hŭngnam coastal strip.

Its principal mission centered on pocket-clearing the area after

NKPA troops and guerrillas had either

infiltrated or fallen behind when their units withdrew from the seaport. To

do this, the paratrooper general created four RCTs

from his three regiments (the 7th, the 15th and the 65th)

and the newly-assigned

ROKA 26th

Regiment. The ROKA 26th had been the first X Corps unit to face

– and be nearly annihilated by – the CCF

in October.

Maj. Gen.

Robert H. “Shorty” Soule, CG 3rd Division, and Col. Harris.

Wŏnsan,

November 1950 (National Archives)

In

the eyes of many, this relatively easy job would somehow hone on skills gone

dull over the postwar years. At this moment the 3rd was at an

alarming state of unpreparedness – “a mess!!!” [emphasis in the original] as

a Military Police sergeant assigned to the division’s 3rd

Military Police Company recalls. “The 7th [Infantry] was

effective from the landing, but the 15th was not an asset, and

sometimes a liability.” The first night ashore, a platoon leader from the

15th Infantry was accidentally shot by one of his own as the

officer checked the alertness of his men.

“As to the 65th,

they were well trained, well used, and could handle their own business.”

When asked how he expected to fight a war with so many untrained units,

Soule’s emphatic answer was that “in the army you led what you had, and

hoped for the best.”

As far as Bill Harris was concerned, an

AOR covering approximately 900 square

miles was too large to be effectively patrolled, let alone defended. His

three battalions were between thirty and forty miles apart, and visiting

them was likened to craving for a bullet on his part.

Heavy engagements erupted alongside the strip; nevertheless,

all enemy attacks were defeated.

The

fourth of December finally presented some “organization” and “direction” for

the 65th, which, for the first three days of the month had been

going back and forth aimlessly inside its AOR,

simply reacting to the changes of orders X Corps had been producing at

machine-gun speed.

The first operation order issued by 3rd Division called for the

Puerto Ricans to relieve the withdrawing 1st Marine Division and

to protect the Changjin Reservoir road from Sudong south to Hamhŭng from

fleeing

NKPA

forces launching diversionary attacks to draw UNC

forces away from the retreating troops. Reunited at Hŭngnam for the first

time since arriving in North Korea, the 65th was assigned the

following missions:

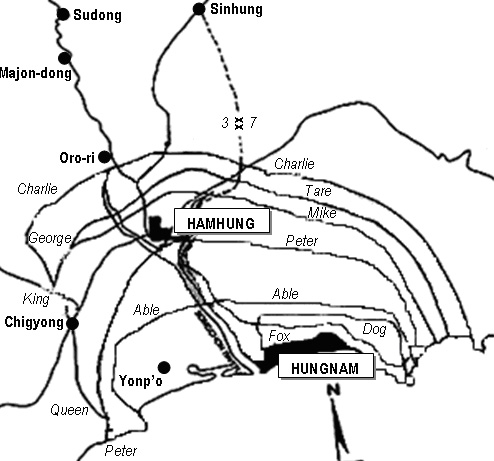

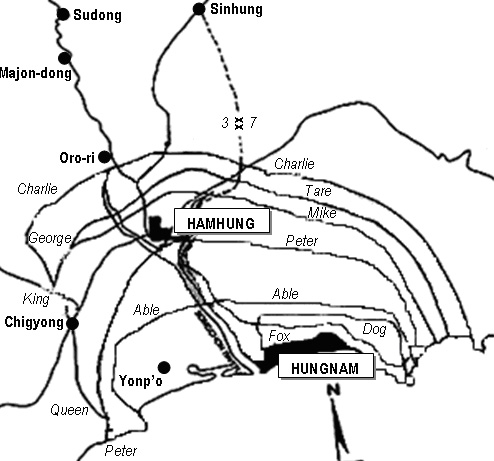

1) Preparing defensive positions on the CHARLIE Line, near

Oro-ri, eight miles northwest of Hamhŭng, from the boundary of the 7th

Division (on the right) to the GEORGE Line on the Tŏngsongch’ŏn River (on

the left) (1/65);

2) Opposing a large enemy force coming from the north;

3) Securing the village of Majŏn-dong, eleven miles north of

the CHARLIE Line (2/65);

4) Clearing the seven-mile stretch of the main supply route

(MSR) from Majŏn-dong to Sudong

of enemy forces (3/65); and

5) Protecting the withdrawal of the 1st Marine

Division headquarters from Hagaru-ri.

Ned Almond’s plan was for the 3rd Division to send

a forward covering force to Chinhŭng-ni, the halfway point of the 40-mile

road between Hagaru-ri and Hŭngnam; wait for the Marines to come barreling

down the mountains; and hold off the CCF

while the Marines withdrew to Sudong. Troops of 2/65 and 3/65 would meet

the withdrawing forces there, and would ensure their safe trucking and

entraining to the Hŭngnam harbor for evacuation to Pusan. The troops on the

perimeter line around “Liberty City” would then be withdrawn from CHARLIE

Line through a series of lines in successive delaying actions until

evacuating the 7th Division under the firing cover of the 3rd

Division’s rearguard.

To

assist the 65th in accomplishing its mission, Shorty Soule

assembled a powerful force commanded by his quick-tempered assistant

division commander, Brig. Gen. Armistead D. Meade. Task Force D (TF

Dog) incorporated elements of 3rd Battalion 7th

RCT, the 92nd

FAB, the 10th and 73rd

Combat Engineer battalions, and the 3rd Reconnaissance and 52nd

Transportation companies into what was likened to a “solve the

unsolvable” or “Cavalry to the rescue” enterprise.

If for whatever obscure reason TF

Dog’s role has gone relatively unrecognized, outshined by the glamour of the

heroic Marine role during the withdrawal, the role of sister task force

Childs has gone virtually inexistent. In fact, so closely intertwined have

been these task forces that yet many members of TF

Childs still believe they had operated under TF

Dog all along. Dubbed after its tactical commander, Lt. Col. George W.

Childs, regimental executive officer of the 65th, this

1,850-strong task force consisted of the core of 2/65 and 3/65, powerfully

supported by units of field artillery, engineer, armor and chemical. Thus,

while TF Dog’s mission would

consist of helping the Marines fight their way southward along the

withdrawal route, TF Childs’

would consist of holding the highlands in front and eventually to the west

of the MSR.

A 75-mm recoilless

rifle position guards the

MSR.

North of Hamhŭng, December 1950 (U.S.

Army Photo)

Another peculiarity accentuating these two forces’ uniqueness has to do with

their racial and ethnic composition of one-third Puerto Rican and two-thirds

black.

While there seems to be no consensus in points of view regarding Ned

Almond’s character, almost all agree in recognizing the general’s subjective

attitude toward “colored” soldiers, result of the disappointing performance

of his 92nd (Negro) Division from World War II. Whether racism

played a major factor in the constitution of task forces Dog and Childs, the

unarguable reality was that, excepting the 65th, the 3rd

Division troops were green to combat.

Soule was to concentrate the remainder of his division

between Chigyŏng and the C-47 Airfield in Yŏnp’o, about four miles southwest

of “Liberty City.”

Both

task forces hit the road in the wee hours of a freezing December 6,

spearheaded by Herman Dammer’s 2/65, which reached Majŏn-dong at 2:30 p.m.

and secured its roads and railroads until TF

Dog’s arrival. Relieved in place, part of 2/65 withdrew to Oro-ri to link

up with Lt. Col. Edward Allen’s 3/65, while George Company 2/65 led

TF Dog’s march north to Sudong. From

their respective positions along one ridge paralleling the road to Hamhŭng,

three companies of 3/65 controlled several miles of adjacencies.

The

Marines Advance in a Different Direction

The

situation up north grew bleaker by the minute. Bill Harris’ West Point

classmate Allan MacLean, regimental commander of the 7th

Division’s 31st RCT,

had been wounded and captured (and ultimately dead) by the

CCF; Lt. Col. Donald C. Faith,

commander of 1/32, had become a KIA;

and TF MacLean–Faith had been

utterly destroyed. The heroism of these men, nevertheless, had not been in

vain, as it had brought the virtual destruction of one

CCF division, allowing the 10,000

Marines and soldiers trapped around the Changjin Reservoir to reach the

relative haven of Hagaru-ri. All along, the “Bayonet” Division would lose

five senior combat commanders during this affair.

Cut off from supply lines and rapidly depleting their

ammunition, Marines and soldiers continued to be exposed and succumbing to

the extreme cold while being surrounded by entire divisions of better

outfitted and better situated fanatic communist troops. On one side, the

formidable terrain allowed the enemy to effectively isolate X Corps; on the

other, the freezing gusts seemed to strip of whatever strengths and fighting

spirit the withdrawing forces might have had during their initial victories

around Changjin. Men collapsed and preferred not to move thereafter,

proving essential for officers and sergeants to stay close to their men and

to drive them to respond even when under attack. Stragglers had to be

kicked and pushed. Whilst hopes of escaping the trap waned, the withdrawal

plan continued as planned.

“We

are just advancing in a different direction,” had been Marine Maj. Gen.

Oliver Prince “O.P.” Smith’s response to a war correspondent when questioned

about the retreat. Firstly, the word was anathema in the Marine Corps

doctrine. Secondly, there was no rear where to retreat to. A toughened

version of O.P.’s candid answer entered the Marine Corps history as, “Retreat,

hell! We’re just attacking in another direction!” New York Herald

Tribune’s Marguerite Higgins, probably the most famous war correspondent

in Korea, and Life Magazine war photographer David Douglas Duncan had

flown to Hagaru-ri to cover the epic withdrawal, but Higgins had been forced

to leave on grounds of her gender and the harrowing hardships yet to be

faced.

It would be partly up to former Marine Duncan to make the Marines withdrawal

the most famous episode of the Korean War.

The

forces departed Hagaru-ri on December 6, stopping briefly at Kot’o-ri,

eleven miles south, while waiting for an airdrop of bridging materials. The

village of Chinhŭng, farther south, marked the first half of their

withdrawal and the rendezvous point with the TF

Dog elements.

During the winter of 1950, which stands as one of the coldest in recorded

history, both warring factions endured the extreme cold weather’s effect not

only upon themselves but upon combat capability as well. Frostbite proved

just as dangerous as the malfunctioning of weapons. Recent declassified

documents show that while the communists had found a way to counter the

malfunctioning of weapons, frostbite remained the gravest enemy by far,

proving more lethal than the formidable overall superiority of the UNC.

For the majority of the warm-blooded Borinqueneers seeing

snow for the first time, the challenge of coping and surviving presented but

an opportunity to employ their resourcefulness. Dressing in layers

compensated for the lack of right winter equipment; carrying their ration

cans under their armpits kept the food warm enough for eating; and keeping

their canteens under their clothing kept the water usable. Individual

weapons were maintained relatively dry. The men had learned that an excess

amount of grease or oil allowed to remain on weapons after they were cleaned

called for a jam and failure to fire. The trick to keep mortar tubes from

shrinking or cracking consisted of setting the mortar base plates on top of

furnaces dug in on the ground and keeping the tubes covered with tarpaulins

until ready for use. In extreme cases, crew-served weapons had to be

urinated upon to be thawed for operation. This exceptional performance in

subzero temperatures so impressed Harris that he would go on to publicize

his men everywhere they went in Korea. Somebody had been selling the Puerto

Rican soldier too low.

TF

Dog’s 92nd FAB elements

support the Marines’ withdrawal.

Chinhŭng-ni, December 1950 (National Archives)

By

December 10 the withdrawing column had grown up to 15,000 men.

CCF hordes were already breathing down

their necks when they came under the protection of the forward infantry and

tank elements of TF

Dog on the outskirts on Chinhŭng-ni. For those men – bearded, starving and

frostbitten – “it sure was a wonderful sight to see friendly troops on the

ridges.”

The sight was even more ecstatic by the time they reached the 3rd

Division perimeter. There, as many as possible were put on some of the 110

trucks provided for the rescue and driven back to Hŭngnam, yet many had to

continue walking. For those, many of whom had not slept in days, the ordeal

was just a bit far from over.

By

the time they reached Sudong, the western highlands of the

MSR for the next seven miles south had

already been secured by the Borinqueneers. The two-month head start in

Korea had given these the astuteness when facing an enemy who relied so much

on terrain features. The tactic they employed to secure the

MSR was the “mouse trap,” which

consisted of faking a retreat along the level grounds of a valley in order

to lure the CCF into a chase,

and once the CCF were well

inside, other Puerto Ricans came swarming down from the highlands,

encircling and annihilating the enemy. By doing this, they had softened the

Chinese pressure enough to allow the Marines and soldiers to get hold of the

highlands and cover the passage of their tanks and vehicles.

“Two

Battalions!”

Men

took advantage of every moment of calm to doze off. Some slept sitting up,

back to back with their buddies; others hugged the warm hoods of the

vehicles. David Duncan had a ball on account of the misery of the men, and

busied himself in taking pictures of his revered “leathernecks,” almost

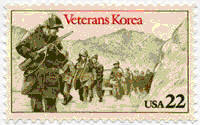

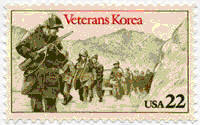

entirely ignoring the 2,300 “doggies” in the column. In what might be taken

as a paradigm of poetic justice, one of his pictures of soldiers would be

immortalized in a 1985 United States Postal Service Korean War Commemorative

Stamp. Misidentified in Clay Blair’s The Forgotten War as a medical

platoon from 2/31, the squad featured in the picture was “not Marines,” but

“soldiers belonging to a Reserve unit, according to what they told me, from

Puerto Rico,” as Duncan himself remarked in the December 25 edition of

Life.

U.S.

Postal Service Korean War Commemorative Stamp (1985)

depicting soldiers of

the 65th Infantry Regiment (USPS)

Despite their excellent performance, the Puerto Ricans could not guarantee

every yard of the way. Later that afternoon and early evening,

CCF elements cut the road, halting the

column. In the ensuing battle the Chinese inflicted about twenty Marine

casualties and destroyed nine trucks. Two Army lieutenant colonels broke

the CCF block; yet the

withdrawal would not proceed undisturbed. TF

Dog’s 3/7 and George/65 would continue to hold off more

CCF attacks throughout the night. The

final group of Marines and soldiers had passed George/65’s defense

positions, the northernmost, when the company was ordered to withdraw and

serve as rearguard for the main body of troops at Majŏn-dong. The order to

cover the company’s withdrawal fell ultimately on Sgt. First Class (Sfc.)

Félix G. Nieves’ platoon, with Nieves’ own squad to cover the withdrawal of

the platoon. As the platoon was completing its withdrawal, an enemy attack

in force developed. Nieves ordered his men to withdraw as he alone defended

the position. In the face of heavy enemy machine gun and small arms fire,

the sergeant killed at least eighteen Chinese before the remainder force

became confused and fled, allowing Nieves’ squad to gain the safety of the

retreating column. Such display of bravado saved the lives of his fellow

Borinqueneers.

While those actions took place up north, the final elements

of the 1st Marine and 7th divisions at Majŏn-dong

boarded trains and trucks in the beginning of their final leg of the trip.

The Borinqueneers gave what food they could spare – mostly C ration sundries

like jelly, biscuits, mustard, fruits, and so forth. For many a starving

soul, a biscuit smeared with mustard likened to a banquet. The withdrawing

troops could not be any more grateful for the gesture of camaraderie

surpassing service branch differences. It is said that when one surprised

Marine officer asked how many divisions had come and the answer was, “Two

battalions from the 65th; Puerto Ricans,” his reaction was, “Two

battalions! But they fight as well as we do!” Clearly, despite

their reversal, the Marines conserved their traditional pride.

Marines and soldiers continued south under the protection of the Puerto

Ricans, all along expecting to defend the sector of “Liberty City” before

their ordeal was over. Unbeknownst to them, the plan to evacuate X Corps

was already in effect. Whereas the CCF

did not seriously interfere with the withdrawal at this point, the

prospective threat they represented called for a vigorous bombardment by

naval gunfire and carrier-based Navy and Marine aircraft. Additional air

cover was available from the C-47 Airfield.

Nocturnal attacks continued throughout the week along the route. At

midnight of the eleventh, elements of Baker/65 faced off a 300-strong

Chinese force north of CHARLIE Line. The Borinqueneers, logically, repelled

the attack; but the CCF

would attack again on the fifteenth, forcing Baker/65 to withdraw to higher

grounds. In the process, the company commander, wounded, fell behind and

refused to be evacuated from the now enemy-held territory. Disregarding his

own safety, a young corporal went back to rescue his commander. No sooner

had he brought the officer back into the company’s position than friendly

artillery and mortar fire started to fall on or near Baker. The corporal

once again volunteered to cross no-man’s land in order to reach a nearby

friendly command post and stop further attacks.

Borinqueneers man a machine gun position south of burning Oro-ri.

December

1950 (National Archives)

This is but one simple example of the Borinqueneer bravado.

These obscure days saw the birth of many a Borinqueneer hero. From

the top brass – like Lt. Col. Childs, whose conspicuous bravery and tireless

energy stimulated morale and contributed greatly to the victory throughout

the five difficult and critical days that his task force was under hostile

fire – to the lower echelons – like young Pvt. Donald Cirino Rivera, who,

whilst exposing himself to intense enemy fire in order to check fields of

fire and direct gun positions, fulfilled his duties of radio operator and

ensured the retake of his company positions.

The

Evacuation

With

the arrival of the first elements in Hŭngnam

between the tenth and the eleventh, X Corps began the evacuation for Pusan.

The corps’ objective was to carry out an orderly evacuation of all

military personnel, equipment and supplies, and certain civilian refugees.

Little equipment was to be left behind, as opposed to the 1945 Okinawa

evacuation. Part of the trophies included several 76-mm Russian-made guns

previously captured from the NKPA.

Even broken-down vehicles would be loaded and lifted out. One Time

Magazine war correspondent described this scenario: “The G.I.s left almost

nothing in wrecked Hungnam except a sardonic sign: ‘WE DON’T WANT THE DAMN

PLACE ANYWAY.’”

Another

burning village, courtesy of the Borinqueneers, (here using ox-carts to

transport their equipment). Near Hŭngnam, December 1950 (National Archives)

In

the personal sense, the evacuation constituted a victory for Ned Almond,

when compared with the disarray on Johnnie Walker’s

EUSAK after the loss of the 2nd Division

and most of its heavy equipment at the Kunu-ri Pass. As far as the refugees

are concerned, Almond strove to live up to his word to evacuate as many as

he could when the option of a ground evacuation was ruled out for safety

reasons. Unfortunately, of the more than 180,000 hoping to evacuate, only

91,000 would.

The

two-star had designated that the first X Corps major unit to be sealifted

would be the Marine division. Priority might have been placed on it because

of the harrowing casualty rate of more than 10,500 since its arrival in

Wŏnsan in October: 40 percent in battle and 60 percent non-battle. While

the Marines out-loaded, Almond would deploy the 3rd and 7th

divisions along the Hamhŭng–Hŭngnam sector, the 3rd taking the

left and the 7th the right. Between December 11 and 14, the

Marines would board 28 ships that, on the fifteenth, would sail for Pusan

amid a blizzard of heroic publicity. The Marines would be followed by the

ROKA I Corps, bound for Mukho, just below the 38th Parallel.

The

7th Division, 2,100 men shorter, followed suit under the covering

fire of the 3rd Division and a formidable force of about 600

planes clobbering the suspected enemy positions outside the constricted

perimeter. The concentration of U.S.

fire laid down on the enemy around the perimeter dwarfed anything ever seen

before in Korea. On the beachhead, self-propelled guns, howitzers, heavy

mortars and flak wagons put out tremendous weight of metal per mile of

front. Offshore, the warships of the Seventh Fleet sent in their own

barrage. Overhead, swarms of Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps planes

sought out and scourged the enemy with napalm, rockets, bombs, and machine

guns. Marine veterans from World War II likened it to Iwo Jima; Army

veterans, to an “Anzio in reverse.”

In one 24-hour period, the combined firepower claimed over 2,600

CCF casualties. Demoralized by such

losses, the CCF sent regrouped

NKPA troops into the fighting,

and by the end of the week it was these who bore the brunt of the battle.

Prisoners said that every time the communists formed up for amassed attacks,

they were dispersed by shell or air attacks. From then on, enemy efforts

died down to simple probing attacks.

Borinqueneer troops cover the withdrawal of the X Corps.

Hŭngnam,

December 1950 (El Mundo)

At

this point, the communists headed off to a bad ending when they muffed

several excellent chances to wreck the X Corps operation. “They knew all

about us,” O.P. Smith would reflect after the battle; “where we were and

what we had. But I can’t understand their tactics. Instead of hitting us

with everything in one place, they kept on hitting us at different places.”

Whether through lack of mobility, of equipment, of tactical judgment, or a

combination of these and other factors, after the Hŭngnam perimeter had been

established, the enemy seemed unable to exploit their greatest asset:

manpower. “The only advantage they have on God’s green earth is numbers.”

In the end, they suffered casualties at least five times that of

U.S. forces.

The Hŭngnam evacuation seemed to be taking longer than

expected. To Ned Almond, nonetheless, it went “the way we planned.”

Whatever the reasons for the delay in wrapping up, the operation was having

two satisfactory results: It was showing the CCF

and the NKPA what the massed

U.S. firepower looked, sounded, and felt like; and it was killing a lot of

communists.

Enemy

attacks renewed in the wee hours of the twenty-second as Shorty Soule’s

three

U.S. RCTs

stood at the second phase line (DOG)

covering the out-loading of the last artillery units of X Corps and the

first of the 3rd Division service units. The brunt of the attack

fell on Howard St. Clair’s 1/65.

Unlike

a

previous company-level attack in which communist troops

wearing

U.S. helmets and winter clothing had been easily repulsed,

the uncanny CCF recurred to a

tactic the Borinqueneers were already familiar with: psychological warfare.

That is, large numbers (approximately

2,500)

and a lot of mass singing, bugling, and cymbal-clashing.

The ensuing battle culminated with morning

light finding about 1,000 CCF

troops lying in the snow, wounded or dead. In spite of incessant air

strafing, and a rain of shells from U.S. artillery and from warships

offshore, the enemy maintained his pressure throughout the day. At night,

star shells and flares illuminated the scene, which was the only practical

way of countering the enemy’s much annoying penchant for night fighting.

Borinqueneers set demolition charges around “Liberty City.”

December 1950 (El Mundo)

The evacuation of X Corps allowed the perimeter to shrink to

no more than ten miles around the Hŭngnam harbor on

the twenty-third, when Soule’s division stood at

the last phase line in preparation for the final withdrawal. Only a small

amount of enemy mortar and artillery fire struck the perimeter troops now,

but that did not keep the division from carrying out the demolition duties

around “Liberty City,” the C-47 Airfield, and surrounding railroads,

storehouses, bridges, and wharves.

As this move took place, the 65th was drawn into a

tighter perimeter defense around the harbor itself. An unexpected yet

welcomed lull allowed for a small awards ceremony in which Lt. Col. Childs,

as well as several Borinqueneers, received accolades from the division

commander. The corps commander would be there as well to present his

customary “impact” awards. Sfc. Nieves, who received the Silver Star for

his actions in Sudong, received a special commendation from Shorty Soule.

Almond recognized the effort of the 65th by presenting the Silver

Star to its regimental commander. A teary-eyed Bill Harris accepted the

Star on behalf of his Borinqueneers, lamenting he could not break it into

pieces and pin one on the chest of every one of his men and another over the

graves of those who had given their lives “on behalf of victory of this

cause and the cause of the democratic nations of the world.”

Maj.

Gen. Edward M. “Ned” Almond, CG X Corps, awards the Silver Star to Col.

Harris.

Hŭngnam,

December 1950 (National Archives)

The division received its orders to withdraw on the

twenty-fourth. The harbor was a sitting duck at this time, its perimeters

outlined by gondola cars rigged with explosives. One false move would have

sent the entire “Marne” Division sky-high.

The

final arrangement behind the last two phase lines, DOG and FOX, showed the 7th

RCT covering the left side, the

65th the middle, and the 15th the right. The order of

withdrawal once the Division Headquarters had out-loaded with all its heavy

equipment and ammunition called for the 7th

RCT to board tank landing craft (LCTs)

at half past noon, followed by the 15th

RCT

minutes later, and then the 65th. Withdrawing with two

neighboring units posed a tricky assignment for the 65th, given

that an exposed flank presented an open door for the

CCF. Accordingly, 1/65 and 3/65 retreated to Blue

Beach, occupied by 2/65, whose retreat was timed to be within minutes of the

departure of the covering force from the 15th

RCT.

Their situation was a precarious one, and the CCF

sought to exploit the present state of affairs by attacking with renewed

strength and utter disregard for the heavy toll they were paying. The enemy

on one side and the sea on the other; the situation had a romantic appeal on

the cornered Borinqueneers, who resorted to bayonets, stones, fists and

boricua-style jiu-jitsu when the Chinese – in extreme cases, carrying

the fight to the water’s edge and even on top of the ridges –

attacked with swords, maces, or nothing else but their own bodies,

staging a bizarre scene that would have certainly put the most imaginative

Hollywood screenwriter to shame. One veteran reminisces: “The only way out

for us was by ship … We opened the way so they [the division] could

retreat.”

“Liberty City” and adjacencies during November and December 1950.

Close naval fire covered the Borinqueneers’ withdrawal. This posed another

tricky maneuver, for if the shells fell short of their intended targets –

the hills surrounding the dockside area – the only Hispanic outfit in the

United States Army was as good as extinct. By 1:30 p.m., under the covering

fire of 2/65, all elements had boarded landing craft. A total of four ships

lifted the RCT: two for its

personnel and two for its equipment. Wave after wave,

LCTs

ferried the drained but proud men to the awaiting ships. Many had to be

pulled up the side meshes of the Liberty class

USS

General H. B. Freeman (TAP

143). “Even on the ship that was to take us out of there,” retired Master

Sgt. Norberto Cartagena recalls, “we had to keep on firing. The Chinese and

the North Koreans were already on the pier.”

Bill

Harris’ command group loaded on the last landing craft with elements of 2/65

at 2:30 p.m. “So far as I know,” Harris would write in his memoirs, “we

were the last to leave the area.”

At 2:37 p.m. the fleet turned away and steamed south.

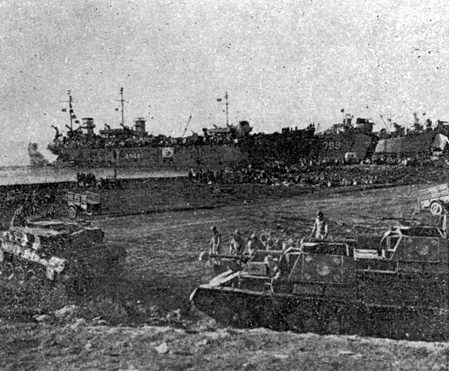

Behind it, the Hŭngnam Harbor sank into the ocean under one

sky-high pillar of smoke.

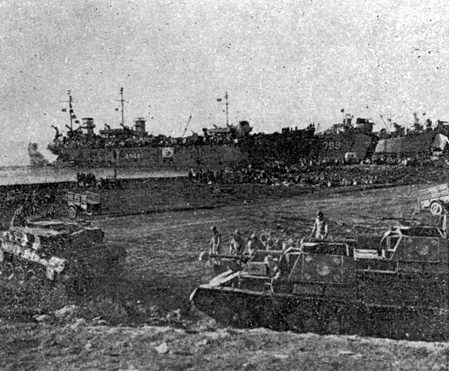

Unidentified troops

(probably Marines) “LEAVING

THE BEACH AT HUNGNAM”in

this David Douglas Duncan picture

featured in the January 8, 1951 edition of Time. The celebrated

photographer topped off his description of the action

with a

sardonic,“If the enemy had used artillery …” to illustrate the grimness of the

scenario surrounding the

X

Corps’ epic withdrawal.

A

Borinqueneer Christmas Carol

All the excitement and gut-tightening anticipation behind,

the 65th prepared to enjoy the most unforgettable Christmas Eve

many had ever had. They had proven to the toughest skeptics that the

Borinqueneers were a fighting force to be reckoned with. It had earned a

place of honor in Marine Corps history. It had survived the Korean winter

at its worst. It had safeguarded the largest sealift since World War II.

The

evacuation itself took 193 shiploads using 109 ships. Two

CCF armies (37,500 men) were

annihilated by X Corps and/or the weather during the withdrawal from

Changjin. Over 3,600 wounded and 200 vehicles were airlifted out. Hŭngnam

was destroyed. In Harris’ opinion, the overall venture constituted “a

logistic and strategic miracle.”

On board the Freeman, the exhausted Puerto Ricans were

treated like honored guests. Many, after enjoying their first hot showers

and hot meals in months, had much to thank the Lord for. Regimental

Catholic chaplain Father Ryan said a Mass, and the men sang “Noche

de Paz” (“Silent Night”) while their Continental comrades sang

“Adeste Fideles.” Colonel Harris commended his men on an unparalleled

performance, reiterating his “complete and unbending confidence in [their]

fighting ability.” Christmas Day in the morning treated the warriors with a

unique breakfast resembling nothing of the cold C rations the men got used

to, in a preamble to the heavenly evening banquet of roast turkey.

The

influx

of troops in Pusan initially overwhelmed that port’s capacity, but by New

Year’s Day the 3rd

Division was on the ground again and ready to assume its duties under

EUSAK’s

I Corps.

The Borinqueneers stood tall and ready for future triumphs in

the Land of Morning Calm.

Inasmuch as the story told in this article draws from the

sources listed below, it does not represent the official version of the

Department of Defense or the United States Army. The contents of the article

and the history it relates are solely the author’s opinion. Furthermore, he

assumes total responsibility for mistakes and/or inaccuracies incurred.

Blair, Clay. The Forgotten War: America in Korea

1950–1953. New York: Times Books, 1988.

Cowart, Glen C. “Christmas Eve: The last day at Hungnam.” The

Watch on the Rhine, December 2001. pp. 22-23.

Donaldson, Leslie. “Recalling 65th Infantry’s

triumphs, tragedies.” The San Juan Star, April 23, 2000. pp. 5-6.

(This article was published simultaneously in Spanish.)

Harris, W. W., Brigadier General, USA (Ret.). Puerto

Rico’s Fighting 65th U.S. Infantry: From San Juan to Chorwan.

California: Presidio Press, 1980.

Mossman, Billy C. Ebb and Flow: November 1950–July 1951.

Washington, D.C.:

Center of Military

History United States Army, 1990.

Norat, José A. Historia

del Regimiento 65 de Infantería

[Spanish:

History of the 65th Infantry Regiment]. San

Juan: La Milagrosa, 1960.

Ruiz, Albor. “Viequenses

Deserve Our Full Support.” New York Daily News, June 8, 2000. p. 2.

Russ, Martin. Breakout: The Chosin Reservoir Campaign,

Korea 1950. New York: Penguin Books, 2000.

Vázquez, Margarita – Author Interview, March 3, 2003. (Sgt.

Vázquez, a member of the Puerto Rico Army National Guard, is the daughter of a

Borinqueneer who served three years in Korea. Special thanks go to

Margarita.)

Villahermosa, Gilberto. Letter to Army Magazine,

September 2002.

“War in Asia.” Time Magazine (as indicated).

Wells, Robert P. Letters to the Author, December 7, 2004;

December 23, 2004; January 6, 2005. (Former Secretary and two-term President

of the 88th Division Association, Mr. Wells served in the 3rd

Division’s 3rd MP Company, an outfit closely linked to the 65th

Infantry Regiment. A special salute goes to Bob.)

______. “What a Christmas dinner!” Military Magazine,

December 2004. p. 26.

About the

Author

Luis Asencio Camacho is a Human Resources Assistant with the Army ROTC on the

Mayagüez Campus of the University of Puerto Rico. He is the author of an

unpublished historical novel on the Borinqueneers. He may be contacted at

[email protected].

Part of this problem of unpreparedness might have to do with the

standardized (perhaps compulsory) integration of ROKA troops into U.S.

Army units. The KATUSA (Korean Augmentation to the U.S. Army) program

created a serious language problem in regards to both proficiency and

terminology, as the Korean language in essence lacked virtually all the

“technological” terms existent in the English language. By the time his

regiment landed in North Korea, Bill Harris had dealt with the problem in

a very particular way: assigning just one KATUSA per squad and

“dispatching” the surplus (over 1,000) back to ROKA units. By then, the

65th’s combat readiness was that of a fully functional unit, as

opposed to the respective readiness of sister regiments, 7th

and 15th, at 50% each.

“War in Asia – The Enemy: Poor Showing,” January 8, 1951.

“War in Asia – Battle of Korea: ‘Anzio in Reverse,’” Time, January

1, 1951.

The operation plan covering the withdrawal of the 65th RCT

originally called for 1/65 and 3/65 to move back from CHARLIE Line to TARE

Line and to hold there until 2/65 leapfrogged them and took up a position

on MIKE Line. The 2/65 would, in turn, hold that position to protect the

1/65 and 3/65 movements to PETER Line, whence, once again, both battalions

would hold while 2/65 reached ABLE Line, and so on. As enemy pressure

grew stronger by the minute, a new revision of the plan was to direct 1/65

and 3/65 to hold on TARE while 2/65 passed through MIKE all the way back

to PETER; then 1/65 and 3/65 leapfrogged to ABLE. Finally, all 65th

RCT elements would move to FOX, the main line of resistance (MLR), site of

the final stand.

José F. Rodríguez, as quoted by The San Juan Star on April 23,

2000.

The issue of which regiment was the last to evacuate the beachhead has

been harshly debated by veterans from both infantry regiments (15th

and 65th). One MP in charge of a ten-man detachment assigned

to protect the 65th during this period recalls the following:

I cannot state to the

minute when either Regiment last embarked its GI’s, but will tell you the

real tale of the 65th. It took a long time for the 65th

to be loaded onto boats because they had to be so carefully channeled

between the Railroad cars that were loaded with explosives to blow up the

stone wharf. When the last units were on their way to the APA Henrico

[Freeman], Colonel Harris and his small group climbed down into

[an] LCVP, and I was one of the group. When we tied up to the steep

stairway of the Henrico it was most difficult to get me and all of

my gear onto the stairs and up them to the deck. A CPO helped me over the

rail, and then took me and what he could carry to a bunk below. Here is

the significant part. We dropped all of my gear, and returned to the deck

BECAUSE [emphasis in the original] the entire port was blown up as we

watched. This was minutes after we got aboard. It was an unforgettable

sight, and told us we were really safe! While we were still at the rail

the Battleship Missouri came close to our port side as it was

leaving the Bay. If anyone of the 15th left land after we did

they would have to have had a speedboat to get away from that explosion.

This is just an opinion. (Bob Wells, in letter to the Author, January 6,

2005)