![]() “MILK RUN”

“MILK RUN” ![]()

By Clement Resto, edited by Danny Nieves,

Supporting documents researched by Danny Nieves.

Information and photos of members of the Belgian Resistance submitted by

Philippe Save, Michel Bauffe, and Marc Jaupart.

Photos of Leonard Mercier and his family submitted by Marie France Mercier

This is a true story of one of my experiences during World War II while serving with the 303rd Bomb Group, Squadron 358, 8th Army Air Force in England in the year 1943. My next mission over Germany was my 7th mission. It was to be a “Milk Run”. The phrase “Milk Run” is used in the Air Force as meaning an easy mission. Since a “Milk Run” is a relatively short hop to the target area, all airmen were happy to receive such an assignment.

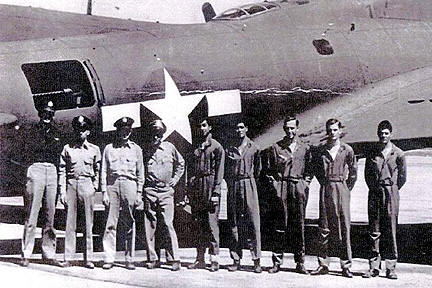

2/Lt. William R. Hartigan's Crew

Left to right - 2/Lt William R. Hartigan - 2nd Lt. Edward N. Goddard - 2nd Lt. Lorin F. Douthett - 2nd Lt. Bernard F. Dorsey -

T/Sgt. Clement Resto - S/Sgt. John W. Lowther - T/Sgt. Robert L. Ward - S/Sgt. Val F. Stoddard - S/Sgt. James T. Ince

On October 19, 1943, I was due to arrive at the airbase, after spending my weekend pass in London. I reminisced about the wonderful time I had enjoying the sights, and hitting the nightspots. As I stepped down from the train in Northampton, my thoughts gradually returned to the grim matters of war. I approached the airbase and headed towards my squadron area, I noticed stillness in the air. The atmosphere was one of solitude. The humming of the Fortress engines was silent and I began to realize that something was wrong, as

there were only two B-17 bombers on the runway strip. One of the B-17’s, was the “Hell’s Angels” and the other was my ship, the “Yankee Doodle Dandy.” They stood there against the horizon like two proud beauties. I asked some of the men, why is everyone so sad? They told me that half of the 8th Air force Bomber Group was shot down on the last mission, which was Schwienfort, Germany. I was saddened to hear of this tragic news. I began to experience a peculiar sensation because some of the men that were shot down in this raid were very good friends of mine. We had gone through basic training and Air Technical Training Schools together in the United States. Little did I realize that my next mission, my seventh, would be my last?

After receiving reinforcements and additional bombers, we started preparations for the next day’s mission. We checked and prepared our equipment. At the briefing the following morning at 0700, we were given instructions and told what our next destination would be. As I sat in the briefing room, I thought of my friends, shot down the day before.

In the briefing room, we sat before a stage where heavy drapes covered the huge navigational map of Europe. This map showed the navigational course that we were to follow going and returning from the target. As the Security Officer drew open the drapes, we were relieved to see that the mission for the day was a short and easy “milk run.” The Security Officer explained the purpose of the mission and other valuable information that would make this a successful mission and aid us in keeping our losses low. One specific order was that we leave behind anything that would serve as a means of identification, in case we went down over enemy territory.

When

the briefing was over, we scrambled for the bombers and each man made the

necessary checks on his oxygen, equipment, etc. As the Engineer, I stood between

the Pilot and Co-pilot, checking instruments and getting the fortress ready for

take-off. All personnel, consisting of eleven aviators, were in position and

waiting for instructions. We then received the signal from the tower to position

our ship on the runway for take-off. Our ship roared down the runway with the

tachometer (air speed indicator) registering our speeds at 50, 60, 70, 80, 90,

100 miles per hour. I called out these speeds to the Pilot who automatically

pulled back on the wheel as we reached 100 miles per hour. With that velocity,

we were off the ground and in flight at 110 miles per hour. We cruised at normal

speed after a smooth take-off. Reaching 10,000 feet, we lined up in formation

and were now in echelon and heading across the English Channel. This day our

squadron was taking the lead, as we were the senior crew. There we were at

28,000 feet with a tailwind of 100 miles per hour.

When

the briefing was over, we scrambled for the bombers and each man made the

necessary checks on his oxygen, equipment, etc. As the Engineer, I stood between

the Pilot and Co-pilot, checking instruments and getting the fortress ready for

take-off. All personnel, consisting of eleven aviators, were in position and

waiting for instructions. We then received the signal from the tower to position

our ship on the runway for take-off. Our ship roared down the runway with the

tachometer (air speed indicator) registering our speeds at 50, 60, 70, 80, 90,

100 miles per hour. I called out these speeds to the Pilot who automatically

pulled back on the wheel as we reached 100 miles per hour. With that velocity,

we were off the ground and in flight at 110 miles per hour. We cruised at normal

speed after a smooth take-off. Reaching 10,000 feet, we lined up in formation

and were now in echelon and heading across the English Channel. This day our

squadron was taking the lead, as we were the senior crew. There we were at

28,000 feet with a tailwind of 100 miles per hour.

Once we crossed the English Channel, I assumed my other duty as the Upper Turret Gunner. Before entering enemy territory, it was necessary to check to be sure that all guns were in working order. I cocked my 50-caliber machine guns and fired a few bursts. I instructed my crews to do likewise before entering into enemy territory.

We were deep over French territory when I spotted about 15 fighters at one o’clock high and alerted the crew of their presence. I positioned myself behind my two machine guns and faced the fighters. I watched them intensely to determine what their next move would be. They circled above us at an altitude of about 35,000 feet. Quickly and without warning, the moment I was waiting for came when two of the fighters peeled off from their group. As the enemy ships descended toward us, I recognized them as ME 109’s. Setting my sights on them, I started firing as they circled the squadron. They swooped down at 11:00 o’clock level and I could see their returning fire as it left the muzzles of their nose guns. They were coming in fast and my machine guns were roaring in short and straight bursts scoring a direct hit on one of them. It burst into flames and went into a tailspin. I was still firing with full fury at the other ship. Almost simultaneously, there was an explosion in my section of the ship. The dome on my turret blew off, the gun barrel bent and brilliant colors, such as those in a color spectrum, flashed before my eyes. Due to the explosion, the sight from my turret tore off and hit me in the mouth and I was dazed for a few seconds. As the flashes and smoke cleared, I made a quick survey of the situation while still in shock. As I looked around, I kept seeing a shadow on my left side and no matter how I turned my head the shadow remained with me. I reached up and touched my left eye; it was bleeding. I became terrified, knowing that I had lost the vision in my left eye. Later I learned that a metal fragment had entered my eye.

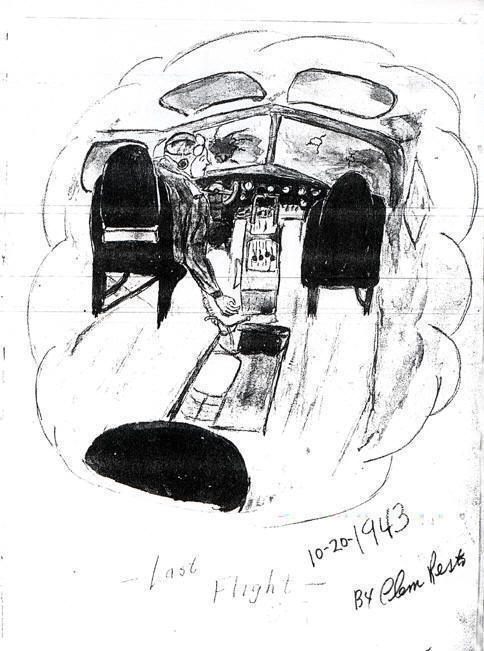

Within seconds, we heard

the faint voice of the pilot over the intercom giving the order to bail out. I

raised my head over the topless turret and with the rushing wind against my

head; I saw that engines one and two were on fire. I lowered myself down

from the turret slowly. I was sitting on the platform of my turret, a little

dizzy, due to the lack of oxygen. I looked around; the oxygen system for the

ship was no longer working. The pilot, apparently hit by shrapnel, was slumped forward in his seat. I could

see by his discoloration that he lacked oxygen. I thought he was dead. We were

in serious trouble at 28,000 feet, with no oxygen and flying a crippled ship.

Luckily, the Pilot set the automatic pilot before he passed out, and we were

still flying in a straight level flight.

The co-pilot, who had collapsed, was

right under my turret. I was scared, and hurt, but kept my head. I put on my

chest chute and helped the co-pilot with his chute. I dragged him to the

bombardier’s hatch and placed him in position to bail out. I gave him a push and

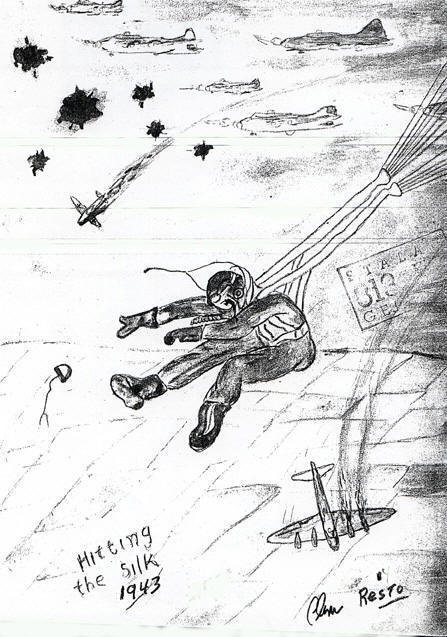

out he went. Jumping right behind him, I fell, tumbling for about 10,000 feet,

reaching an altitude where oxygen was available. I then opened

The pilot, apparently hit by shrapnel, was slumped forward in his seat. I could

see by his discoloration that he lacked oxygen. I thought he was dead. We were

in serious trouble at 28,000 feet, with no oxygen and flying a crippled ship.

Luckily, the Pilot set the automatic pilot before he passed out, and we were

still flying in a straight level flight.

The co-pilot, who had collapsed, was

right under my turret. I was scared, and hurt, but kept my head. I put on my

chest chute and helped the co-pilot with his chute. I dragged him to the

bombardier’s hatch and placed him in position to bail out. I gave him a push and

out he went. Jumping right behind him, I fell, tumbling for about 10,000 feet,

reaching an altitude where oxygen was available. I then opened

my

chute. As I fell, a Messerschmitt buzzed me in an attempt to force the air out

of my parachute, so that it would collapse and I would hit the ground. Thus,

there would be no evidence of foul play, which is in keeping with the Geneva

Convention Regulations of war. But lady luck was with me as my parachute just

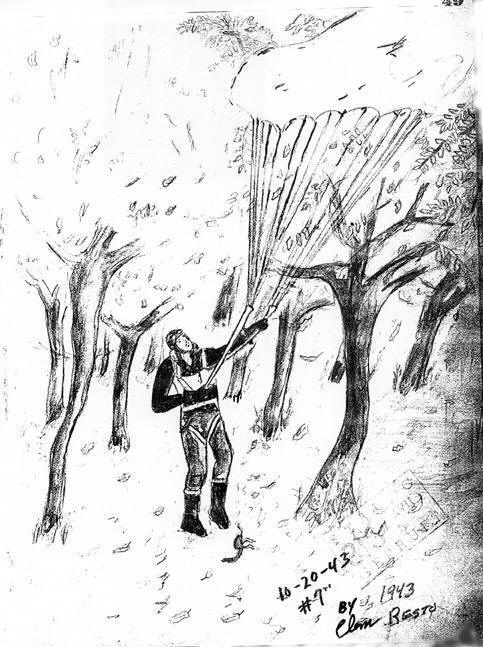

swayed and I descended at normal speed, landing in a forest in Belgium, two

kilometers from the French border. My parachute caught in a tree branch. I cut

myself loose; I did not want the parachute seen from the air by the enemy so I

took it down from the tree.

my

chute. As I fell, a Messerschmitt buzzed me in an attempt to force the air out

of my parachute, so that it would collapse and I would hit the ground. Thus,

there would be no evidence of foul play, which is in keeping with the Geneva

Convention Regulations of war. But lady luck was with me as my parachute just

swayed and I descended at normal speed, landing in a forest in Belgium, two

kilometers from the French border. My parachute caught in a tree branch. I cut

myself loose; I did not want the parachute seen from the air by the enemy so I

took it down from the tree.

There I was, at 2 p.m. on October 20, 1943, in enemy territory, not knowing what would happen next. I administered first aid to my sightless eye and applied a bandage.

I began walking through the

forest to get away from the area where I landed. I

wanted

to reach a dirt road, which I had spotted from the air. After walking for about

15 or 20 minutes, I hid in some thick bushes to rest. At this point, all sorts

of things went through my mind. I tried to remember my training, on how to

survive in the event that we had to bail out over enemy territory. Suddenly I

heard a noise coming from the road. Cautiously, I parted the bushes and saw

about ten cows coming down the road, led by an elderly woman, and a young girl.

I did not attempt to contact them, because I knew they could not help me. The

minutes dragged by, and after what must have been an hour, I heard another

noise. This time it was a German Border Patrol on bicycles. I was very still,

and could hear my heart pounding as they drove past only a few feet from where I

was hiding.

wanted

to reach a dirt road, which I had spotted from the air. After walking for about

15 or 20 minutes, I hid in some thick bushes to rest. At this point, all sorts

of things went through my mind. I tried to remember my training, on how to

survive in the event that we had to bail out over enemy territory. Suddenly I

heard a noise coming from the road. Cautiously, I parted the bushes and saw

about ten cows coming down the road, led by an elderly woman, and a young girl.

I did not attempt to contact them, because I knew they could not help me. The

minutes dragged by, and after what must have been an hour, I heard another

noise. This time it was a German Border Patrol on bicycles. I was very still,

and could hear my heart pounding as they drove past only a few feet from where I

was hiding.

Time passed very slowly. I

became restless, cold, and very hungry but I dared not venture out in my

uniform. Just as I was getting ready to settle down for the night, I heard

someone whistling at a distance. Again, I peered through the bushes and waited.

This time it was a man walking alone. I figured that now was my chance to get

help. At the squadron, we were told that whenever we found ourselves in a

situation like this, to try to get assistance from one individual instead of two

persons, because one person would not have to worry that a companion might turn

him over to Gestapo agents. I took a chance and came out of the bushes calling

to the

![]()

![]()

![]()

stranger.

He turned in a frightened manner and looked at me as though I was something or

someone from outer space. He did not move – just stood there. Again, I greeted

him, this time in French. “Bon jour Monsieur, Yo Americano Aviador! Coprende

vous?” He started to walk slowly towards me his first words were, “Americano?” I

said, “Oui, Monsieur.” He took my arm, and led the way back to the bushes.

Speaking French, he asked about my injuries. I, being of Hispanic decent,

answered him in Spanish, thinking perhaps that he would understand Spanish

better than he would understand English. I did not know whether this was the

reason but between his French and my Spanish, we were able to make ourselves

understood. I told him that I needed some civilian clothes and a doctor. He

seemed to understand and pointing to my wristwatch, indicated that he would be

back in an hour. He was going to cross the French border to see his brother and

would then be back. The signal would be a whistle. He left and, as he walked

away, all I could see was a shadow disappearing into the bushes. It was pitch

dark in the forest now, and all I could hear was the rustling of the leaves as

the wind blew through the trees. It seemed an eternity until I heard that

whistle, which meant that he had returned. I whistled back so that he could find

me in the dark. He came through the bushes with a bundle under his arm, opened

it and handed me a crew neck sweater, a cap and a suit jacket. I changed into

them right away. Then he bundled my flight suit and slung it over his shoulder

and, at his direction, we headed along the road towards his home. Finally we

came to a town. I never thought that I would be walking through a German

occupied town. There I was under their very noses, dressed in civilian clothes,

crossing their main street as if I were a native of this country. It was rather

dark and I could pass undetected. I had the feeling that a Gestapo agent was on

every corner watching every move I made. Finally, we arrived at his house. Upon

opening the door, the first person I saw was his wife who stood petrified. He

explained that I was an American aviator, and that he was helping me.

Immediately I noticed a warm expression spread over her face, indicating that

she accepted me and was sympathetic to my plight.

stranger.

He turned in a frightened manner and looked at me as though I was something or

someone from outer space. He did not move – just stood there. Again, I greeted

him, this time in French. “Bon jour Monsieur, Yo Americano Aviador! Coprende

vous?” He started to walk slowly towards me his first words were, “Americano?” I

said, “Oui, Monsieur.” He took my arm, and led the way back to the bushes.

Speaking French, he asked about my injuries. I, being of Hispanic decent,

answered him in Spanish, thinking perhaps that he would understand Spanish

better than he would understand English. I did not know whether this was the

reason but between his French and my Spanish, we were able to make ourselves

understood. I told him that I needed some civilian clothes and a doctor. He

seemed to understand and pointing to my wristwatch, indicated that he would be

back in an hour. He was going to cross the French border to see his brother and

would then be back. The signal would be a whistle. He left and, as he walked

away, all I could see was a shadow disappearing into the bushes. It was pitch

dark in the forest now, and all I could hear was the rustling of the leaves as

the wind blew through the trees. It seemed an eternity until I heard that

whistle, which meant that he had returned. I whistled back so that he could find

me in the dark. He came through the bushes with a bundle under his arm, opened

it and handed me a crew neck sweater, a cap and a suit jacket. I changed into

them right away. Then he bundled my flight suit and slung it over his shoulder

and, at his direction, we headed along the road towards his home. Finally we

came to a town. I never thought that I would be walking through a German

occupied town. There I was under their very noses, dressed in civilian clothes,

crossing their main street as if I were a native of this country. It was rather

dark and I could pass undetected. I had the feeling that a Gestapo agent was on

every corner watching every move I made. Finally, we arrived at his house. Upon

opening the door, the first person I saw was his wife who stood petrified. He

explained that I was an American aviator, and that he was helping me.

Immediately I noticed a warm expression spread over her face, indicating that

she accepted me and was sympathetic to my plight.

I was indebted to the people who helped me at a time when I needed help most. I was a complete stranger, and yet they shared everything with me. They prepared a Boric Acid solution for my swollen eye. Each night his grandmother, would bring a basin and wash my feet, after washing my feet, she would tuck me in bed, and place a hot brick wrapped in a towel at my feet, for the room was cold. Help of this kind, you can never forget. I shall never forget the kindness that I received from this family. The following day I tried to convey to them that they must contact the Belgian Resistance, in order to help me leave the country. However, Leonard’s idea was for me to stay in his house until the end of the war. Leonard, even showed me a picture of his sister in law, and with a smile on his face remarked “Fiancée oui !” I said very nice, but that at this time I could not accept his proposal. My duty was to try to rejoin my squadron in England. Finally, he said, “I’ll try and see what I can do, but you know this is very dangerous.” He left the house to make the contact. Late in the evening, he returned, he told me that he had made contact with the Belgian Resistance, and that I would have two visitors the following day. I thanked him, and he told me not to worry.

During my stay, Leonard and I learned a lot about each other. We were very much acquainted by now, and could converse and exchange different opinions. That night we spent the evening talking, and looking at some old French movie magazines that he had prior to the war. The next day at about 10:00 a.m., there was a knock at the door; Leonard looked at me, and told me to hide in the adjacent room. All I could hear was two men talking in French. After about five minutes, he appeared and told me to come out, that everything was all right. As I stepped into the room, I saw the two men. After the introductions, we sat down. One of the men spoke English and to my surprise gave me an American cigarette, its brand was Wings. He explained that he was able to get them through the black market. We finally settled down to business. He briefed me on what he was going to do. We shook hands again and he said, “Until tomorrow, at 10:00 a.m.; be ready to leave.” Leonard and I then sat down in the living room and conversed some more on the past and the future after the war and other topics concerning the present situation.

The next day while I was having

tea with Leonard, the two men that I was waiting for arrived. I told them that I

was ready to go with them. It was not easy to say good-bye to Leonard and his

family. As we shook hands, he embraced me. I told him that I would write to him,

when the war ended, then I left waving my hand as I departed through the outside

door. My two escorts had a small panel truck parked at the curb, with the back

doors open, I crawled into the back of the truck and we started to move. I could

not see in which direction we were going, as there were no windows in the truck.

It seemed like we had been riding for hours, when the truck finally came to a

halt. The back door opened and I climbed out. As I looked around me, I saw that

I was at a farm, operated by two

elderly women. They greeted me in French and told me to enter the house; it was

a two-story house and seemed like a safe hideout. The two men told me; before

they left that, I would spend two or three days in this house, then transfer to

another place. The purpose of this was to prevent the Gestapo agents from

following our trail. The two elderly women then introduced me to two men, who

came out from a back room. One, called Pierre, and the other Francis, I took for

granted that they were also part of the Belgian Resistance. Pierre seemed more

friendly and on the second day of my stay in this house, he started to converse

with me. He told me a story of one of his exploits in the Belgian Resistance

when he blew up a train in a railroad yard guarded by the Germans. This led me

to believe that he was a professional saboteur, and it seemed that he enjoyed

telling this story, because from the time I arrived, he repeated the same story

to me, and each time he told it, he had a wild look in his eye’s and would go

into a hilarious laughter, like he enjoyed this assignment.

two

elderly women. They greeted me in French and told me to enter the house; it was

a two-story house and seemed like a safe hideout. The two men told me; before

they left that, I would spend two or three days in this house, then transfer to

another place. The purpose of this was to prevent the Gestapo agents from

following our trail. The two elderly women then introduced me to two men, who

came out from a back room. One, called Pierre, and the other Francis, I took for

granted that they were also part of the Belgian Resistance. Pierre seemed more

friendly and on the second day of my stay in this house, he started to converse

with me. He told me a story of one of his exploits in the Belgian Resistance

when he blew up a train in a railroad yard guarded by the Germans. This led me

to believe that he was a professional saboteur, and it seemed that he enjoyed

telling this story, because from the time I arrived, he repeated the same story

to me, and each time he told it, he had a wild look in his eye’s and would go

into a hilarious laughter, like he enjoyed this assignment.

On the third day, with the

same precaution they took before, I moved to another house. This time th e

house was in the town, escorted I walked into a hall, a door opened from one of

the rooms and a man told me to step in. As I walked into the room, I was

surprised to see four of my crewmembers sitting on a long couch. Joyfully we

embraced one another. It was a wonderful feeling to see that they wee alive and

well. As we talked, they told me that this was the last stop over. From here on,

we would get passports and a guide for our journey through France. I noticed

that the occupants of the house had a radio. I asked my co-pilot how these

people managed to have a radio, when they when they had been confiscated by the

Germans, and that no one in German-occupied territory was supposed to have a

radio in their homes. He answered me by saying, “Well I guess being in the

underground, they are doing it without the German’s knowledge.” I did not

question it any further as my headaches were getting worse. The next day my

co-pilot and I were to be the first to go and make the contact with the

Resistance group in Brussels. Again, I questioned this action. I stated to my

co-pilot, why should we go fifty miles north from the French border to pick up

some passports and a guide, when we could cross the border from where we are,

which is only a mile and a half. This did not sound logical to me, and I was

suspicious of the group who were supposed to be helping us escape from this part

of the country. “My co-pilot said to me, “They must know

what they’re doing, they must have been doing this sort of thing right along.” I

decided to forget the incident and tried to concentrate on how we were going to

get out of this enemy held country. The

e

house was in the town, escorted I walked into a hall, a door opened from one of

the rooms and a man told me to step in. As I walked into the room, I was

surprised to see four of my crewmembers sitting on a long couch. Joyfully we

embraced one another. It was a wonderful feeling to see that they wee alive and

well. As we talked, they told me that this was the last stop over. From here on,

we would get passports and a guide for our journey through France. I noticed

that the occupants of the house had a radio. I asked my co-pilot how these

people managed to have a radio, when they when they had been confiscated by the

Germans, and that no one in German-occupied territory was supposed to have a

radio in their homes. He answered me by saying, “Well I guess being in the

underground, they are doing it without the German’s knowledge.” I did not

question it any further as my headaches were getting worse. The next day my

co-pilot and I were to be the first to go and make the contact with the

Resistance group in Brussels. Again, I questioned this action. I stated to my

co-pilot, why should we go fifty miles north from the French border to pick up

some passports and a guide, when we could cross the border from where we are,

which is only a mile and a half. This did not sound logical to me, and I was

suspicious of the group who were supposed to be helping us escape from this part

of the country. “My co-pilot said to me, “They must know

what they’re doing, they must have been doing this sort of thing right along.” I

decided to forget the incident and tried to concentrate on how we were going to

get out of this enemy held country. The

following

day we were told by the man in charge of the house where we were staying, that

two of us would be leaving, that he had made contact with one of the outside

underground agents, and made arrangement to transfer two of the American fliers

to another house, and that this would be the last stop on contacts. A guide and

passport would be provided in order to be able to travel through France. We all

wondered who would be the first to go. At noon that day, the man in charge said

that two of us would leave today. Much to my surprise, he had chosen my co-pilot

and me as the first pair to keep the rendezvous with the outside agent. The

proprietor of the house that we were hiding told us of the arrangements that he

had made on the outside which were as follows: My co-pilot and I were to follow

him into town, where we were to sit in the tavern and wait for him, until he

brought back the train tickets and further instructions. Therefore, we sat at

this tavern, playing cards, as if we were steady customers in this

establishment. We had ordered a few rounds of beer already and the time was

three o’clock in the afternoon, we were starting to get worried now, because it

was two hours since he left us. We had finished our third round of beer, so I

summoned the Madam to come to our table. As she approached our table I showed

her the empty bottle, she picked it up and brought back a full one, and I said

“Merci, Madam, we didn’t speak to much for fear of being found out that we were

Americans. I noticed that the tavern was beginning to get crowded with old and

middle aged men, coming in for their evening brew. Now we were really sweating

under the collar. I thought, what if one of these men in this place approached

us, and asked us what game we were playing, or where were we from. However, luck

was with us, because just then we spotted our man coming through the tavern door

and walking towards us, with a smile on his lips. He stood by our table, looked

around, and said, “Everything is arranged, follow me.” As we went through the

tavern door he gave us the run down as follows; “You two men are going to follow

that girl in a red dress at a distance,” as we looked across the street we saw

the girl, and shook our heads with pleasure. He continued talking, “She will

board the train to Brussels, where she will then lead you to your next contact.”

With that explanation, he then gave us our train tickets and shook our hands,

and we started to follow the girl in the red dress. She boarded the train and we

did the likewise. The girl had a lovely figure one could not help but follow.

She sat opposite us with the middle aisle between us. She never looked at us;

her face was always facing the train window, looking out. It took four hours to

get to Brussels, and all the time the train was traveling, she never looked or

spoke a word to us. The train, blacked out – completely, we just sat in semi

darkness, while the train traveled through the night and I wondered what was

ahead for my co-pilot and me. The train finally started to slow down and as I

looked out the window, we were pulling into Brussels Station, our last stop. The

young girl got up from her seat and started walking towards the train door. We

got up and started to follow her, as per instructions, and stepped off the

train, right behind her. As we looked around the station, we were amazed at the

tremendous size of the train station and of the German soldiers all over the

place with steel helmets on and full equipment with swastika bands on their arms

and fixed bayonets on their rifles. I did not say a word again to my co-pilot, I

was afraid that someone would hear our conversation. We continued to follow the

girl, my, she was beautiful – and what a lovely walk she had. She was now

approaching the outside of the train station and at the corner of the street she

stopped to talk with two men, one was short with a French beret on his head and

the other was tall and well dressed. The man with the beret approached us with a

smile and said, “Ah-Monsieur - welcome,” and shook our hands at the same time as

if we were old time friends. In the excitement of the introduction, I noticed

that the girl had disappeared from the area where we were standing. As we stood

there in the still of the night, you could hear the clicking of heels from the

soldiers inside the railroad station. My thoughts were far away when the short

man with the beret interrupted my thoughts, and said in broken English, “Come

now, step inside the car.” I stepped in, I noticed two more men in the back seat

and they gave me the appearance of two F.B.I. men from the States, we sat facing

them; they were still as statue’s. The little man with the beret was sitting

between us, he started to question my co-pilot, as the car started to pull away

from the train station. With a grin on his face, he asked about his age, what

his mission was, and other questions, which are top secret with the U.S. Air

Force. – Then my co-pilot answered that it was just a routine mission. With this

statement, he was not giving the little man any military information on what the

target was at the time of the mission, when we got shot down. At this time I

interrupted the little man by asking a few questions of my own, like where were

we going, if the place he was taking us was going to feed us, and about the

passport, and the guide. He answered me, a little annoyed at my questioning him,

and said, “Yes! You will get everything when we get there.” I continued to ask

him questions like, is not it hard for you to obtain gasoline for this car. He

said, “No, we have connections, why do you ask?” I answered, because this seems

to be the only car in the street, and he replied, “Have you, been in Brussels

before?” I answered, “No, I am just inquiring for my peace of mind.” Then he

said not to worry, that they know how to handle all situations. We were riding

for about fifteen minutes when the car came to a halt. Suddenly the little man

with the beret spoke in a commanding voice, “Come! Get out!” We obeyed his

command with a questioning look, as my co-pilot, and I got

following

day we were told by the man in charge of the house where we were staying, that

two of us would be leaving, that he had made contact with one of the outside

underground agents, and made arrangement to transfer two of the American fliers

to another house, and that this would be the last stop on contacts. A guide and

passport would be provided in order to be able to travel through France. We all

wondered who would be the first to go. At noon that day, the man in charge said

that two of us would leave today. Much to my surprise, he had chosen my co-pilot

and me as the first pair to keep the rendezvous with the outside agent. The

proprietor of the house that we were hiding told us of the arrangements that he

had made on the outside which were as follows: My co-pilot and I were to follow

him into town, where we were to sit in the tavern and wait for him, until he

brought back the train tickets and further instructions. Therefore, we sat at

this tavern, playing cards, as if we were steady customers in this

establishment. We had ordered a few rounds of beer already and the time was

three o’clock in the afternoon, we were starting to get worried now, because it

was two hours since he left us. We had finished our third round of beer, so I

summoned the Madam to come to our table. As she approached our table I showed

her the empty bottle, she picked it up and brought back a full one, and I said

“Merci, Madam, we didn’t speak to much for fear of being found out that we were

Americans. I noticed that the tavern was beginning to get crowded with old and

middle aged men, coming in for their evening brew. Now we were really sweating

under the collar. I thought, what if one of these men in this place approached

us, and asked us what game we were playing, or where were we from. However, luck

was with us, because just then we spotted our man coming through the tavern door

and walking towards us, with a smile on his lips. He stood by our table, looked

around, and said, “Everything is arranged, follow me.” As we went through the

tavern door he gave us the run down as follows; “You two men are going to follow

that girl in a red dress at a distance,” as we looked across the street we saw

the girl, and shook our heads with pleasure. He continued talking, “She will

board the train to Brussels, where she will then lead you to your next contact.”

With that explanation, he then gave us our train tickets and shook our hands,

and we started to follow the girl in the red dress. She boarded the train and we

did the likewise. The girl had a lovely figure one could not help but follow.

She sat opposite us with the middle aisle between us. She never looked at us;

her face was always facing the train window, looking out. It took four hours to

get to Brussels, and all the time the train was traveling, she never looked or

spoke a word to us. The train, blacked out – completely, we just sat in semi

darkness, while the train traveled through the night and I wondered what was

ahead for my co-pilot and me. The train finally started to slow down and as I

looked out the window, we were pulling into Brussels Station, our last stop. The

young girl got up from her seat and started walking towards the train door. We

got up and started to follow her, as per instructions, and stepped off the

train, right behind her. As we looked around the station, we were amazed at the

tremendous size of the train station and of the German soldiers all over the

place with steel helmets on and full equipment with swastika bands on their arms

and fixed bayonets on their rifles. I did not say a word again to my co-pilot, I

was afraid that someone would hear our conversation. We continued to follow the

girl, my, she was beautiful – and what a lovely walk she had. She was now

approaching the outside of the train station and at the corner of the street she

stopped to talk with two men, one was short with a French beret on his head and

the other was tall and well dressed. The man with the beret approached us with a

smile and said, “Ah-Monsieur - welcome,” and shook our hands at the same time as

if we were old time friends. In the excitement of the introduction, I noticed

that the girl had disappeared from the area where we were standing. As we stood

there in the still of the night, you could hear the clicking of heels from the

soldiers inside the railroad station. My thoughts were far away when the short

man with the beret interrupted my thoughts, and said in broken English, “Come

now, step inside the car.” I stepped in, I noticed two more men in the back seat

and they gave me the appearance of two F.B.I. men from the States, we sat facing

them; they were still as statue’s. The little man with the beret was sitting

between us, he started to question my co-pilot, as the car started to pull away

from the train station. With a grin on his face, he asked about his age, what

his mission was, and other questions, which are top secret with the U.S. Air

Force. – Then my co-pilot answered that it was just a routine mission. With this

statement, he was not giving the little man any military information on what the

target was at the time of the mission, when we got shot down. At this time I

interrupted the little man by asking a few questions of my own, like where were

we going, if the place he was taking us was going to feed us, and about the

passport, and the guide. He answered me, a little annoyed at my questioning him,

and said, “Yes! You will get everything when we get there.” I continued to ask

him questions like, is not it hard for you to obtain gasoline for this car. He

said, “No, we have connections, why do you ask?” I answered, because this seems

to be the only car in the street, and he replied, “Have you, been in Brussels

before?” I answered, “No, I am just inquiring for my peace of mind.” Then he

said not to worry, that they know how to handle all situations. We were riding

for about fifteen minutes when the car came to a halt. Suddenly the little man

with the beret spoke in a commanding voice, “Come! Get out!” We obeyed his

command with a questioning look, as my co-pilot, and I got

out

of the car we looked around. It was pitch dark and all I could see was a

tremendous heavy door, with iron knocker, and as I looked upward, it appeared to

be some sort of a castle. As the little man knocked on the door, you could hear

an eerie hollowness inside the building. I questioned my co-pilot with a

frightful look, “Where the heck are we?” The big doors opened slowly with a

squeaking noise. Then I saw the unexpected. We froze to the spot, for inside the

building stood Nazi soldiers lined up on steps leading up to a corridor. We

snapped out of this shocking trance, when the little man, this time with

authority in his voice commanded, “Come! - Come! – Step inside, this is the end

of the line for you Yankee Americans.” We walked inside, and from the entrance,

he directed us to an office at the end of the corridor. Inside the office, I

noticed three Nazi’s in dark uniforms and two soldiers in regular army green

uniforms. At the corner of the office sat a blonde woman in her mid thirties. We

stood in the middle of the office without saying a word. It seemed as though a

million eyes were watching, and that at dawn we would executed. Then as the

little man spoke, I knew that this was the beginning of the interrogation.

“Please state your name, rank, what your mission was and the target.” I

interrupted him and said, “Listen to me; we are prisoners of war now! All we are

supposed to tell you is our name, rank and serial number, in accordance with the

Geneva Convention and articles of War.” He was most obliging and said, “Of

course, you are correct in your statement, and I consider it a waste of time to

continue this interrogation because we know everything.” He continued to give

information in our conversation that I was not aware of. He said, “We, the

Gestapo know that two American bombers were shot down, each having an estimated

eleven men on board. We found one airman dead, and from his identification tag,

we obtained his name and serial number.” As he mentioned his name, I was stunned

for a few seconds, but did not let on that I knew who it was or show any

emotion, for I knew it was my assistant Radio man, a Youngman about 20 years of

age, from St. Louis, Mo.. He said that two aviators were still missing, but he

hoped to capture them soon. He kept talking to impress us with their superiority

in espionage and intelligence capabilities. With this, he motioned to the German

soldiers to take us away. Escorted we were led through a long corridor, which

led to an iron gate. A guard opened the gate, and we went through it. My

co-pilot and I were both assigned cells. As I stood in the middle of the jail

cell, I could see a table with a burlap straw mattress under it. The cell had a

small window

out

of the car we looked around. It was pitch dark and all I could see was a

tremendous heavy door, with iron knocker, and as I looked upward, it appeared to

be some sort of a castle. As the little man knocked on the door, you could hear

an eerie hollowness inside the building. I questioned my co-pilot with a

frightful look, “Where the heck are we?” The big doors opened slowly with a

squeaking noise. Then I saw the unexpected. We froze to the spot, for inside the

building stood Nazi soldiers lined up on steps leading up to a corridor. We

snapped out of this shocking trance, when the little man, this time with

authority in his voice commanded, “Come! - Come! – Step inside, this is the end

of the line for you Yankee Americans.” We walked inside, and from the entrance,

he directed us to an office at the end of the corridor. Inside the office, I

noticed three Nazi’s in dark uniforms and two soldiers in regular army green

uniforms. At the corner of the office sat a blonde woman in her mid thirties. We

stood in the middle of the office without saying a word. It seemed as though a

million eyes were watching, and that at dawn we would executed. Then as the

little man spoke, I knew that this was the beginning of the interrogation.

“Please state your name, rank, what your mission was and the target.” I

interrupted him and said, “Listen to me; we are prisoners of war now! All we are

supposed to tell you is our name, rank and serial number, in accordance with the

Geneva Convention and articles of War.” He was most obliging and said, “Of

course, you are correct in your statement, and I consider it a waste of time to

continue this interrogation because we know everything.” He continued to give

information in our conversation that I was not aware of. He said, “We, the

Gestapo know that two American bombers were shot down, each having an estimated

eleven men on board. We found one airman dead, and from his identification tag,

we obtained his name and serial number.” As he mentioned his name, I was stunned

for a few seconds, but did not let on that I knew who it was or show any

emotion, for I knew it was my assistant Radio man, a Youngman about 20 years of

age, from St. Louis, Mo.. He said that two aviators were still missing, but he

hoped to capture them soon. He kept talking to impress us with their superiority

in espionage and intelligence capabilities. With this, he motioned to the German

soldiers to take us away. Escorted we were led through a long corridor, which

led to an iron gate. A guard opened the gate, and we went through it. My

co-pilot and I were both assigned cells. As I stood in the middle of the jail

cell, I could see a table with a burlap straw mattress under it. The cell had a

small window with iron bars about seven feet from the floor, and as I stood on a small stool

to look out the window, all I could see was a swastika flag waving in the breeze

from a tower of the prison. I found myself in a state of solitude, not knowing

what would be happing next, and never being in a situation like this, I did not

know what to think and who to turn to for consultation, so I turned to my

religious faith for consolation, and said a few prayers.

with iron bars about seven feet from the floor, and as I stood on a small stool

to look out the window, all I could see was a swastika flag waving in the breeze

from a tower of the prison. I found myself in a state of solitude, not knowing

what would be happing next, and never being in a situation like this, I did not

know what to think and who to turn to for consultation, so I turned to my

religious faith for consolation, and said a few prayers.

That night I could not sleep. My headache was getting worst, and the situation I was in did not help any. I had a very restless night. As the morning approached and the sunlight’s rays came through the window bars and brightened the cell room, I realized that this was not a dream that I actually was in a prison cell, and not back at the airbase. I sat motionless on the straw mattress bed getting my thoughts together, and realizing that there was nobody around me to say good morning to. However, I gave thanks to God that I was alive and was still able to function under abnormal conditions. The rattling of keys against the iron door to my cell distracted me. As I looked to the door, it was the guard; he gave me a bowl of hot water and a piece of bread. That was breakfast, -- I looked at it, then I looked at him, as if to say, “Is this all?” He shrugged his shoulders, and walked out, locking the door behind him. I made the best of it and said to myself, it could be worst. I sat on a small stool in the cell and drank the hot water, for it was cold outside and the cell was just as cold, and the hot water would at least warm me up. While in conferment, I summoned the guard and asked him, if I could get a doctor to examine my eye, which I could not see out of, and to give me something for my headache, but to no avail. He said that I would get medical attention when I reached my permanent prison camp. I thought that this was unfair to American wounded aviators. I went to the corner of my cell and sat down on the stool. The days were long and lonely. As I glanced at the walls of my cell, I found myself reading the different inscriptions written on it. The inscriptions, written by the prisoners that were in this cell before me, were all kinds of sayings and poetry. I said to myself, I might as well do the same thing, and I started writing on the wall and playing tic tack toe with the metal spoon that was given to me. Now I know what they meant by the old saying, watch for the handwriting on the wall. My interpretation is that it refers to people that have gone through the same problems and experiences that you are going through, and that they have left their handwriting on the wall to give your courage and mental stability for the coming ordeal. The days continued to roll by and the food was nothing to talk about, and the room service was lousy. On the fourth day at about 8:00 p.m., I heard a tapping noise coming from a set of pipes that ran along the wall and disappeared through the intersecting wall to a section behind my cell. I listen closely to the tapping, it sounded like an old phrase that they use to say in the good old U.S.A. that went like this; “Hey, and a hair cut – shampoo”. I picked up my metal spoon and returned the same sound affects, on the pipes in my cell, and much to my surprise, who ever it was, came back with the same rhythmical sound. So I said to myself that only soldiers or military men know that rhythmic phrase, has to be an American. A joyful felling seem to take place in my heart, as I continued to tap on the pipes with more enthusiasm, I crept closer to the wall, where the pipes disappeared. I began digging with my spoon by the wall where the pipes went through, and I could hear digging noises from behind the wall. I stopped digging, placed my head close to the pipe going through the wall, and said “hey! You in there, are you an American?” The voice answered back, and again I felt a sensation of happiness, for I recognized the voice, it was Ralph Moffett, the photographer, one of the crewmembers from the bomber. Then I said, “Ralph, is that you?” He answered back! “Clem is that you?” We were so happy to hear each other’s voices in this forsaken place that we did not talk. Finally, we calmed down, and started exchanging information on what had happened to us, from the time we went down, to the present time. We continued to converse, I told him that I had been in my cell for four days, and he told me, that he had gotten there three days ago. The questions and answers that we exchanged between us were endless, but it gave us something to pass the time away, and we had our own private communication system, through the pipes, that protruded through the wall into the next cell. The next day about 1:00 PM, the guard opened my cell door and said in German, “Oust!”[1] – Which I knew meant to get out. Therefore, I walked out of my cell, and he directed me to stand in front of the cell door, which I obeyed. As I look around other prisoners were standing in front of their cell doors. I glanced to my extreme left side, I saw my crewmember Ralph, and he gave me a wink, which I returned inconspicuously so the German guard would not be aware that we knew each other.

To be continued

[1] I've been told later after the war, that "oust" was a Belgian expression to say get out. My guard was probably a Belgian!