ON APRIL 22, 1951, U.N. forces

in Korea held a 100-mile-long defensive line stretching the entire width

of the peninsula at roughly the

38th Parallel.

Defending this line was the U.S. 3rd, 24th and 25th Infantry

divisions in the west, the 1st Marine and 2nd Infantry divisions in the central

sector

and the 7th Infantry Division in the east. The 1st Cavalry Division was

held in reserve. Troops from other U.N. nations and South Korea rounded out

the line.

Facing the allied units were nine armies comprising

27 Chinese and North Korean divisions totaling some 250,000 men.

The main goal for U.N. forces was to hold their positions,

and, if necessary, fall back in orderly fashion to protect Seoul. As the new

commander of the 8th Army, Lt. Gen. James A. Van Fleet, said, "For the time

being, real estate was not important; the main task was to kill Communists."

GIs had ample opportunity.

'WHAT WE HAVE BEEN WAITING FOR'

Van Fleet and Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway (who took over as supreme commander

in Far East at the beginning of April) knew the Chinese Communist Forces

(CCF) were ready to attack, but didn't know when. Two CCF soldiers-captured

in two separate incidents on April 22-divulged plans for a major offensive

around 9 that night. It was, as one U.S. officer said that evening, "what

we have been waiting for."

Sure enough, at about 10 p.m. nearly a quarter million

Communist "came swarming out of the night by the light of a full, but by

this time smoked hazed moon, blowing bugles and horns and shooting flares,"

as Clay Blair wrote in his book The Forgotten War: America in Korea

1950-1953. "It was the start of the biggest battle of the Korean War."

The main thrust of the CCF attack initially smashed into

the U.S. 65th Infantry Regiment, made up of Puerto Ricans, with an attached

unit from the Philippines, along Line Wyoming.

"They really hit us," said 65th commander Col. William

W. Harris. "I believe the enemy attack bounced off us and spilled over on

both sides."

U.S. artillery men across the front were ready for the

Communist onslaught.

"The gullies in front of us are already full of Chinese

dead," one U.S. gunner told a Time correspondent, "and we intend to

keep adding to the pile."

During the night of April 22 the "Wolfhounds" of the

27th Infantry Regiment fought ferociously, often in hand-to-hand combat.

Helping out, the 8th, 90th and 176th Field Artillery battalions (FABs)

trained their guns on the enemy.

"It was a machine gunner's and artillery man's dream,"

said Gen. George B. Barth, commander of the 25th Division's artillery. "After

about 30 minutes, the Reds had enough. The Wolfhounds were not bothered anymore

that day."

The full story of the CCF attack hit the central sector

hard, and units were forced to begin a systematic withdrawal. The 92nd FAB,

as well as the 1st and 7th Marines of the 1st Marine Division, fell back and

formed a perimeter near Chunchon, providing a haven for troops during the

retreat. Early on April 24, the CCF swarmed it.

"What ensued was one of the most astonishing valorous

Army actions of the Korean War," Blair wrote. "Acting in the role of infantry,

[92nd commander Lt.Col. Leon F.] Lavoie's men manned rifles, carbines and

machine guns and promptly delivered an awesome stream of fire into the oncoming

enemy."

The 92nd FAB suffered four KIA and 11 WIA, but killed

179 Chinese on the perimeter alone.

Later that night, the CCF attacked the command post of

the 35th Infantry Regiment. "All three battalions of the 35th were cut off,"

Barth said, "but that fine regiment fought its way clear by battalion."

As the Chinese rushed toward the town of Kapyong, 30

miles northeast of Seoul, they ran headlong into Australian and Canadian

infantrymen of the Commonwealth Brigade supported by Company A of the U.S.

72nd Tank Battalion, 2nd Division.

"During the fight [1st Lt. Kenneth] Koch's American tankers

performed magnificently," Blair wrote. "They bravely supported the Australian

infantry with direct fire, brought ammo forward and evacuated wounded, killing

CCF coming and going."

Three of the 72nd's tankers were killed and 12 wounded.

Koch and one of his platoon leaders, W. Donald Miller, earned Distinguished

Service Crosses for their "extraordinary heroism" that day. The 72nd, as

well as the Australian and Canadian battalions, won the Presidential Unit

Citation.

'ONE OF THE MOST GALLANT FIGHTS'

On the morning of April 25, the U.S. 3rd Division's 7th Infantry Regiment

was ordered to withdraw south toward Uijongbu, only 10 miles north of Seoul.

The regiment's 1st and 3rd battalions - "hollow-eyed from fatigue"-

had held their ground during the night. But as the 3rd Battalion began withdrawing,

the CCF launched a massive frontal assault. According to Blair, A and B companies

of the 1st Battalion then "staged one of the most gallant fights of the war."

Cpl. John Essebagger, Jr., of A Co., and Cpl. Clair Goodblood

of B Co., both earned posthumous Medals of Honor, while the 1st Battalion

received the Presidential Unit Citation. Altogether, for men of the 7th Regiment

earned MOHs that day: Pfc. Charles Gilliland and Cpl. Hiroshi H. Miyamura

were the other two recipients.

Another withdrawal, also on April 25, ended in tragedy

for the 24th Division's 5th Regimental Combat Team (RCT)- which included

the 8th Ranger Company and the 555th FAB. Trouble first occurred when the

CCF surrounded and trapped the Rangers. A tank platoon was able to rescue

only 65 Rangers. Later, the CCF ambushed the 555th as it was moving toward

Uijongbu.

"What resulted was another terrible slaughter," Blair

wrote. "About 100 artillerymen were lost or missing."

One commander recorded simply that it was a "gruesome

scene."

'SPENDING PEOPLE LIKE AMMUNITION'

In the end, the U.S. strategy of orderly withdrawals wore down the CCF.

"They attack, and we shoot them down," an officer told

a Time reporter. "Then we pull back, and they have to do it all over again.

They're spending people the way we spend ammunition."

Slowly, U.N. forces pulled back to Line Lincoln (or Golden)

- the last line of defense protecting Seoul. Trenches and bunkers fortified

with machine guns, recoilless rifles, flame throwers, barbed wire, anti personnel

mines, booby traps and "thousands" of drums filled with napalm and white phosphorus

secured the line.

On the night of April 28, the enemy attacked Line Lincoln,

resulting in 1,241 dead North Koreans and "an estimated 1,000 dead and wounded"

Chinese. Afterward, the enemy withdrew to the hills around Uijongbu.

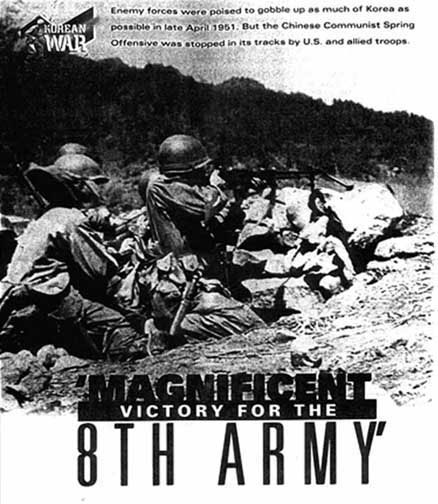

Over eight days of fighting, U.N. troops sustained about

7,000 casualties, versus 70,000 for the CCF. It was "another magnificent

victory for the 8th Army," Blair wrote, denying "the enemy his primary objective,

Seoul."

BATTLE CASUALTIES

Killed in Action.....314

Wounded in Action..1600

HOME PAGE